While self-portraiture is nearly as old as art itself, the photographic selfie emerged as a globally recognized phenomenon only recently, as a result of the rising “attention economy” and its growing appetite for likes, followers, retweets and fame. Google estimates some 24 billion selfies were taken in a year via 200 million Google accounts alone, which signals that the phenomenon far from being marginal.

Selfies can be taken by virtually anyone, and companies and brands have recognized the magnetic “power” in making a selfie a key element of marketing campaigns and social-media content strategies. Yet brands are increasingly aware – and often uncomfortably so – that individuals’ selfies constitute a whole new form of brand co-creation. Based on my research, I will examine how people use “brand selfies” to express their identities as complex assemblages of things, objects, and brands and how that engenders new challenges for branding.

Selfies and self-portraiture in historical perspective

The selfie phenomenon has important connections with the idea of self-portraits in fine arts that emerged in the 16th Century. Already classic works of artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt, for example, featured paintings, engravings and drawings of the artist face-to-face with the spectator. These images often featured the artist “in action” in the artist’s studio, usually holding the pencils, brushes and colour palette in hand, in order to give the impression that the image was spontaneous and authentic in nature. But it was also not uncommon to these early self-portraits that the artist posed in fine clothing and staged apparel, or that he was playfully engaging with various image genres of the time. For instance, self-portraits were often fused with historical scenes or even still-life images.

The self-portrait shares much in common with the visual genre called “snapshot aesthetic”, commonly in use in photography and commercial images, and not least in ads. Snapshot relies on the authentic feeling of images snapped “on the go” of our daily lives. As described by Iqani and Schroeder (2015), these casual, everyday images helps us narrate and make sense of our selves but also communicate our existence to those around us.

When examined in the light of broader history of self-portraiture and photography it becomes quickly clear that classifying and pathologising selfies as simple acts of narcissism and ego-play would overlook important critical commentaries and reflexivity that this visual form potentially offers. Notably, many famous self-portraits have sought out for representational agency in order to make visible issues related to power and politics, including gender, as explained by art historian Derek Murray (2015).

Yet it is important to keep in mind that the self-portrait and selfie differ in several respects. For one, self-portraits were historically rare and usually produced by the elite and the celebrated. It was not until the boom of popular photography around the turn of 20th Century that it was democratised as a key genre of image making. And it was the rise of smartphones and easy online access that made selfie an everyday and ever-present spectacle and practice.

Selfies and the rise of attention economy

The emergence of selfie phenomenon can be partly explained by peoples’ increasingly important drive for attentional capital in the forms of quantifiable likes, shares and followers. The selfie is a symptom of the attention economy, as it draws on intimate and sometimes revealing images in a magnet-like manner. As a result, “instafame” has allured celebrities and stars, rappers and gangsters, presidents and popes to take selfies, but they are not reserved just for the elite. More than 296,417,695 images have been tagged in Instagram alone, when writing this article, suggesting that selfies can be found in just about everyone’s social media profiles.

Research by Eagar and Dann (2016) identifies selfies as an important “self-branding” practice. They also point out various kinds of popular selfies that proliferate quickly, including autobiography, parody, propaganda, romance, self-help, travel, and the coffee-table-and-book selfies. Other ubiquitous trends include selfies at the gym, toilet, funeral, museum, swimming pool, in front of mirror, or alongside luxury or other objects, or while wearing a hijab – and with or without a selfie-stick.

Yet emerging research has found that selfies are not only the product of narcissism but they also may entail a feeling of being in control of one’s own expression as well as empowerment. Selfies have been considered as potent ways for negotiating one’s identity-related tensions, such those related to body ideals, gender, ethnicity, sexuality or religion – or even ways to combat censorship in countries with limited freedom of speech. Selfies have also been recognized as a powerful cultural form because of their ability to transcend linguistic and cultural boundaries.

Brand selfies and consumer microcelebrity

New digital technologies are evidently changing the ways in which meanings and identity of both consumers and brands are constructed. This is why, in my ongoing research on champagne, I decided to study how consumers post selfies featuring some of the most popular champagne brands.

By means of visual analysis of consumer-made selfies on champagne brand Instagram accounts, I was able to uncover some key dynamics that explain how the brand selfies impact and potentially contest even well-established brands, such as Moët & Chandon, Dom Pérignon, or Veuve Clicquot, the three most talked-about champagne brands online in my data. A total of 6,820 images were gathered during six weeks in April/May 2014, from which a random sample of 120 images were analysed in detail. The objective was to compare how brand account images differ from consumer-made selfie-images, which constituted as much as 40% of all brand-tagged images, to illuminate their distinct nature.

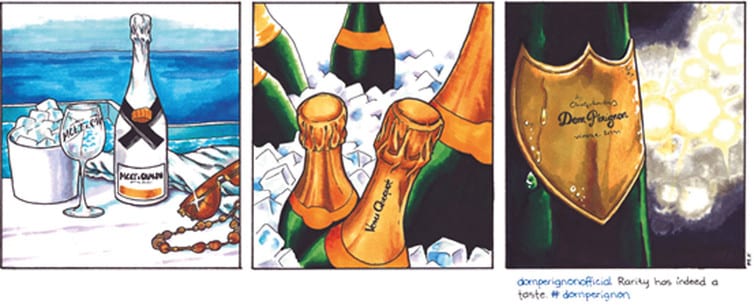

It became quickly clear that the studied brand-controlled accounts did not use selfies in their visual communications, and even the presence of people (only 25% of images on average) or faces (13%) was rare. Instead, the brands’ postings often echoed typical champagne advertising images depicting a “still life” of inanimate objects, artefacts and scenery mainly focused on the product close-up – including the brand logo (75%), bottle(s) (63%), wine (25%), and bubbles (13%). They also ensured, as one might imagine, that no other brands were present or identifiable. All attention was reserved for the focal champagne brand and its principal, historically shaped associations that most often included “heritage/tradition” (55%), “class/status” (45%), and even “magic” (22%) (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Champagne brands expressed in Instagram brand accounts. Maria Federley.

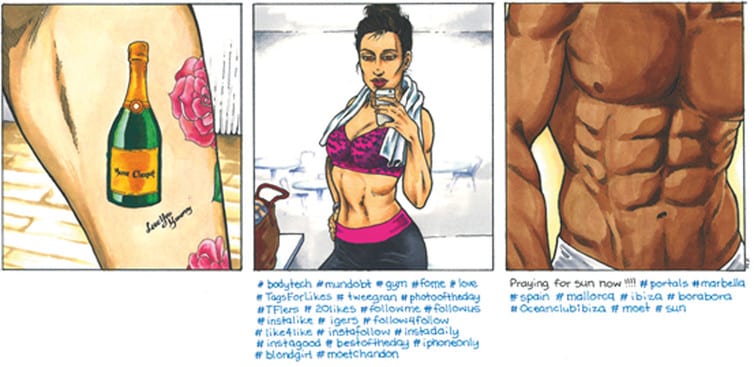

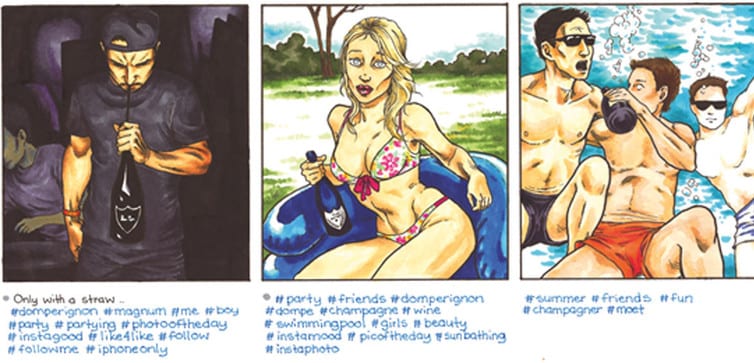

Consumers’ brand selfies presented sharp and visible contrast to these “official” brand images. While the appearance of bottles, wine and bubbles in selfie-images was as frequent as in the brand images, they presented a large number of human bodies (95% of selfie images and 1.5 people per image on average), with as many as 53% of the images featuring face(s). This shift in focus impacts the overall feeling of the images in significant ways. Notably, the presence of human bodies and identifiable faces break the brand’s singularity and gives it an often banalized expression.

In addition, consumers’ brand selfies were not focused on a single champagne brand, but nearly 40% of the images contained or tagged several brands at once. Instead of being focused on the brand, the selfies were systematically centred on the “self”, making the brand necessarily more peripheral (see Figure 2). More often than not, the brand was only mentioned with a hashtag in textual commentary but not visible in the image.

What emerges from the consumers’ brand selfies is an incontestable expression of what I call “microcelebrity”. This highly popular category, constituting 67% of all the consumer-made images, can be understood as a collection of visual practices and strategies that mimic celebrities’ postings aimed to signal fame and attractiveness to others. For example, common brand selfies entail “mirror selfies”, “gym selfies”, “bathroom selfies”, “bikini selfies”, and “party selfies”, in other words, “ordinary” people posing as if they were famous stars. These postings commonly joined with follower and attention-seeking hashtags such as #follow4follow”, #followme, #like4like and #pickoftheday (see Figure 3).

Above all, these findings reveal that selfies as a new form of visual self-presentation practice have come to offer alternative constructions of brands with new kinds of material and expressive features. Notably, they indicate that selfies (and the self) are becoming the nodal point at which official brand images and consumer microcelebrity assemblages intersect. This powerful shift potentially undermines stable, historically built symbolic and material properties of heritage brands, and makes visible a profound heterogeneity of alternative and often chaotic brand images – at least from the point of view of the brand manager.

New challenges for branding

Companies and marketing scholars have long understood that social media have accelerated processes of brand co-creation with customers. Yet very often this phenomenon has been considered only in terms of online consumer-to-brand or consumer-to-consumer verbal dialogues or narratives – hence, word-of-mouth – leaving the visual aspects aside. New forms of visual practices, including the selfie, force the marketers to see and re-consider the visual dimension of their co-creation strategies. The problem is that until recently, most social-media monitoring tools base their analysis on text, not images or video. We thus seem to lack comprehensive tools and even vocabulary for addressing the arguably slippery, elusive but also excessive and voluminous visual. This makes the brand managers’ tasks increasingly difficult.

Although experienced marketing professionals may have an intuitive understanding towards the visual, in my research I have hoped to offer more concrete approaches in this regard. Through visual content analysis of both official and consumer-made champagne Instagram images, I worked to understand the kinds of expressive and material assemblages of identities that the social media images construct. This allowed us to map out the focal elements that consumer-generated images – although most often arguably unintentionally – reinforce in the official brand expressions and meanings, and also those that effectively disrupt and destabilize them.

For example, it was not uncommon that the studied official champagne brand accounts, and perhaps by accident, expressed symbolic and material elements in their postings that were largely in contradiction and dissonance, at least in terms of stylistic consistency, with their historically stabilized brand vision (for example, postings with “wrong” kinds of champagne glasses, or combining champagne with “wrong” kinds of subcultural symbols).

How can companies manage brand co-creation through selfies? Despite the above-described challenges, I believe that powerfully resonant, charismatic, and meaningful brands can always play an important role in leading the creative production of social-media images and interactions. On a practical level, this could simply mean campaigns where brands teach people to take “desired” types of images with the “right” types of expressive and material ingredients.

However, the question at stake is more fundamental: a contemporary brand can no longer rely on strategies that follow a logic that aims to “control” and “own” every association and aspect about their brand. Instead, they need to embrace a whole new conception of a brand which is more “open source” by default. This means that successful brands need to allow for more diversity and flexibility in the expressions and meanings that “fit” it. An excellent example is the GoPro brand that relies exclusively on consumer-created visual communications across all of their (official) communications. In a similar manner, successful brands will need to relinquish control – at least in a much greater degree – to gain resonance with the selfie-obsessed social media world.

This article was previously published on the Conversation website, on April 27, 2017.

Consumer researcher by training, I am a Finnish associate professor of marketing specialised in studying consumer experiences and culture and how they are mediated, impacted, and shaped through digital media. In my research I put emphasis on and develop creative audiovisual methods including videography in order to address the complexity of experience including temporality, space, movement, embodiment, affect, and materiality. I was the recipient of The Sidney J. Levy Award (2015) for my dissertation research. I have professional experience in marketing and business development in a leading Finnish FMCG company, Valio Ltd. and running my own company specialised in management training and consulting around the issue of customer experience. I also run the Lifestyle Research Center at emlyon business school.

More information on Joonas Rokka:

• His CV online

• His ResearchGate page

• His Academia page

Further reading…

- Rokka, J., Canniford, R. 2016. Heterotopian selfies: how social media destabilizes brand assemblages. European Journal of Marketing, 50 (9/10): 1789-1813. DOI: 10.1108/EJM-08-2015-0517.

View abstract online - Rokka, J. 2016. Champagne: marketplace icon. Consumption Markets and Culture, Forthcoming. DOI: 10.1080/10253866.2016.1177990.

View abstract online - Rokka, J. 2016. How 4 ‘myths’ made champagne a global marketplace icon. Knowledge@emlyon, December 21st, 2016.

Read article online - Eagar, T., Dann, S. 2016. Classifying the narrated #selfie: genre typing human-branding activity. European Journal of Marketing, 50 (9/10) : 1835-1857. DOI: 10.1108/EJM-07-2015-0509.

View abstract online - Murray, D.C. 2015. Notes to self: the visual culture of selfies in the age of social media. Consumption Markets & Culture, 18 (6) : 490-516. DOI: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1052967.

View abstract online

Recent Comments