Innovation is the process of converting an idea or an invention into a good or a service, creating a value that users are prepared to adopt and/or pay for. Although they invest heavily in R&D, this conversion process remains elusive for numerous well-established companies.

The directors of these companies are aware of this: a 2015 Boston Consulting Group study revealed that the majority of directors of the 1,500 companies surveyed are not very satisfied with their innovation processes, finding them too slow, too conservative and poorly coordinated.

Many companies rely on corporate entrepreneurship to remedy the shortcomings in their existing innovation processes. But corporate entrepreneurship has its limitations and is not always the most suitable approach. This note attempts to identify the specific characteristics of corporate entrepreneurship and the situations in which it is a particularly appropriate method of innovation.

Corporate entrepreneurship

There are numerous definitions of corporate entrepreneurship. Sharma and Chrisman define it as “the process whereby an individual or a group of individuals, in association with an existing organization, create a new organization or instigate renewal or innovation within that organization.”

Wolcott and Lippitz define it as “the process by which teams within an established company conceive, foster, launch and manage a new business that is distinct from the parent company but leverages the parent’s assets, market position, capabilities or other resources.”

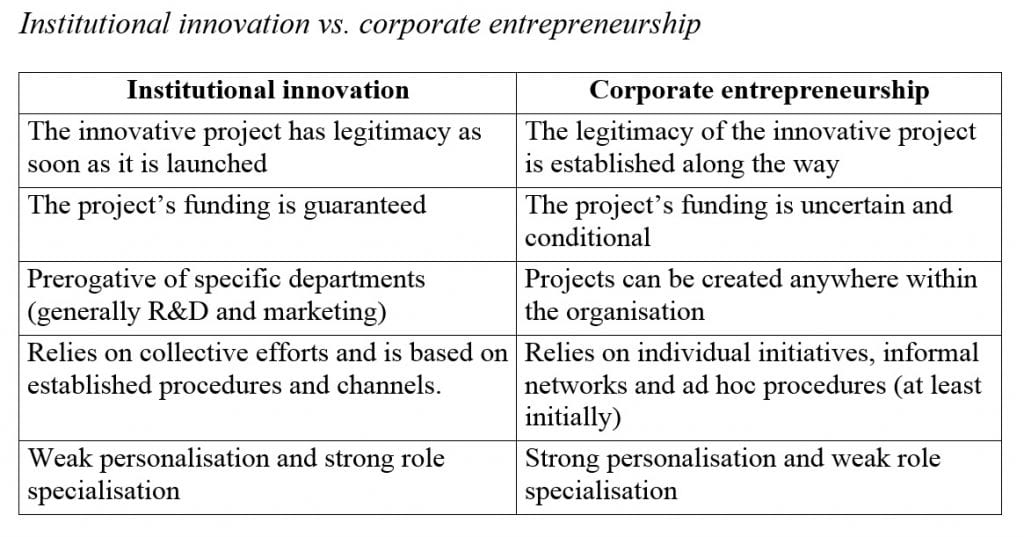

As an innovation method, corporate entrepreneurship is not based on institutionalised processes and competencies but on the flair and improvisation of individuals. It places individuals and their social interactions at the heart of the innovation process. Corporate entrepreneurs are autonomous and committed employees who behave like partners of the organisation rather than cogs in the process. Furthermore, corporate entrepreneurs not only contribute to the innovation process as specialists, they also take responsibility for all aspects of their project during its different phases. They cannot rely on a predetermined allocation of funds and instead need to constantly “sell” their project internally in order to obtain the resources they need. It is also common for corporate entrepreneurs to work on their project in parallel with their other activities, at least initially. They draw on informal networks to obtain resources and support and do not necessarily follow standard procedures. Finally, corporate entrepreneurs are prepared to take personal responsibility for the success or failure of their project.

Corporate entrepreneurs’ autonomy, commitment and gradual modus operandi allow them to accelerate the development cycle and to increase their project’s chances of success while minimising the costs and risks inherent in pursuing innovative activities. But they are also isolated and often face strong asymmetry in their relationship with the organisation, which may ultimately weaken the development of their project. In addition, their incremental approach can prove to be disadvantageous when scaling up their project. Innovating “entrepreneurially” rather than institutionally has advantages and disadvantages: it is therefore important to identify situations in which the advantages are sure to exceed the disadvantages.

Two situations particularly suited to corporate entrepreneurship

1. When rapidity and responsiveness are key success factors

As individuals play a central role in the process, corporate entrepreneurship offers the advantages of rapidity and responsiveness, because individuals – not organisations – are able to mentally combine the key dimensions (technologies, resources, workflows and market requirements) of an innovative project, to rapidly integrate new information and to immediately alter their course of action. Corporate entrepreneurship can therefore be used to accelerate development cycles and to fine-tune the response to market demands. On the other hand, corporate entrepreneurship is less suitable when reliability is a key success factor. In such cases, institutional innovation with its formalised processes and decision-making rules is better equipped to guarantee a predictable end result, aligned with stringent safety and performance requirements. Although corporate entrepreneurship can occupy a central place in the development of new activities in industries such as fashion, food or services, it cannot play the same role in the nuclear, aerospace, finance or public services industries, for example.

2. The company has expertise in a core technology (or technologies) with multiple applications

3M and W.L. Gore and Associates are two large companies whose strong capacity for innovation relies heavily on corporate entrepreneurship. They are structured as large incubators where individual initiatives are given plenty of freedom when it comes to designing new products. These strongly diversified companies roll out their core technologies to hundreds of applications, each very different from the other but all with the potential to occupy profitable niches. Because of the emphasis it places on individual initiative, entrepreneurial innovation encourages proliferation and diversity and multiplies the number of new products launched each year. Whether at 3M or Gore, the products launched all leverage perfectly mastered core technologies, which form a shared knowledge base available to potential innovators. Conversely, companies that focus on a single product (automotive, aerospace, microprocessors) and whose design and production processes are based on the integration of multiple technologies are less likely to benefit from the initiative and individual improvisation that characterises entrepreneurial innovation.

Does this mean that there is no room for corporate entrepreneurship in certain companies? The answer to this question is “no”! Corporate entrepreneurship has a vast field of application that extends beyond product innovation: it can be used to improve processes and systems, to create new internal skills, to develop new marketing and promotion methods, to offer ancillary services, etc. What’s more, corporate entrepreneurship not only generates economic benefits, but also helps to motivate teams and to decompartmentalise the organisation and as such can play a role in any company.

Professor of strategy and corporate entrepreneurship, I hold a PhD from The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. My research interests also include innovative pedagogy and blended course design. Before joining emlyon business school’s faculty, I used to work as a strategy consultant at the Boston Consulting Group and run my own consulting practice.

More information on Véronique Bouchard:

• Her CV online

• Her ResearchGate page

• Her Google Scholar page

Further readings…

- Bouchard V., Fayolle A. (2017). Corporate Entrepreneuship. Routledge, 168 p. ISBN 9781138813687.

Read abstract online

- Ringel M., Taylor A., Zablit H. (2015). The most innovative companies 2015: four factors that differentiate leaders. The Boston Consulting Group, 22 p.

Read report online - Sharma P., Chrisman S. J. J. (2007). Toward a Reconciliation of the Definitional Issues in the Field of Corporate Entrepreneurship. In: Cuervo Á., Ribeiro D., Roig S. (eds) Entrepreneurship. Springer, 83-103. DOI 10.1007/978-3-540-48543-8_4.

Read abstract online

Recent Comments